Previous article: intro to Ansible

Here we are with our journey in the Ansible world, this time we’ll look at the other fundamental features of its structure and use.

Play and playbook: what is the difference?

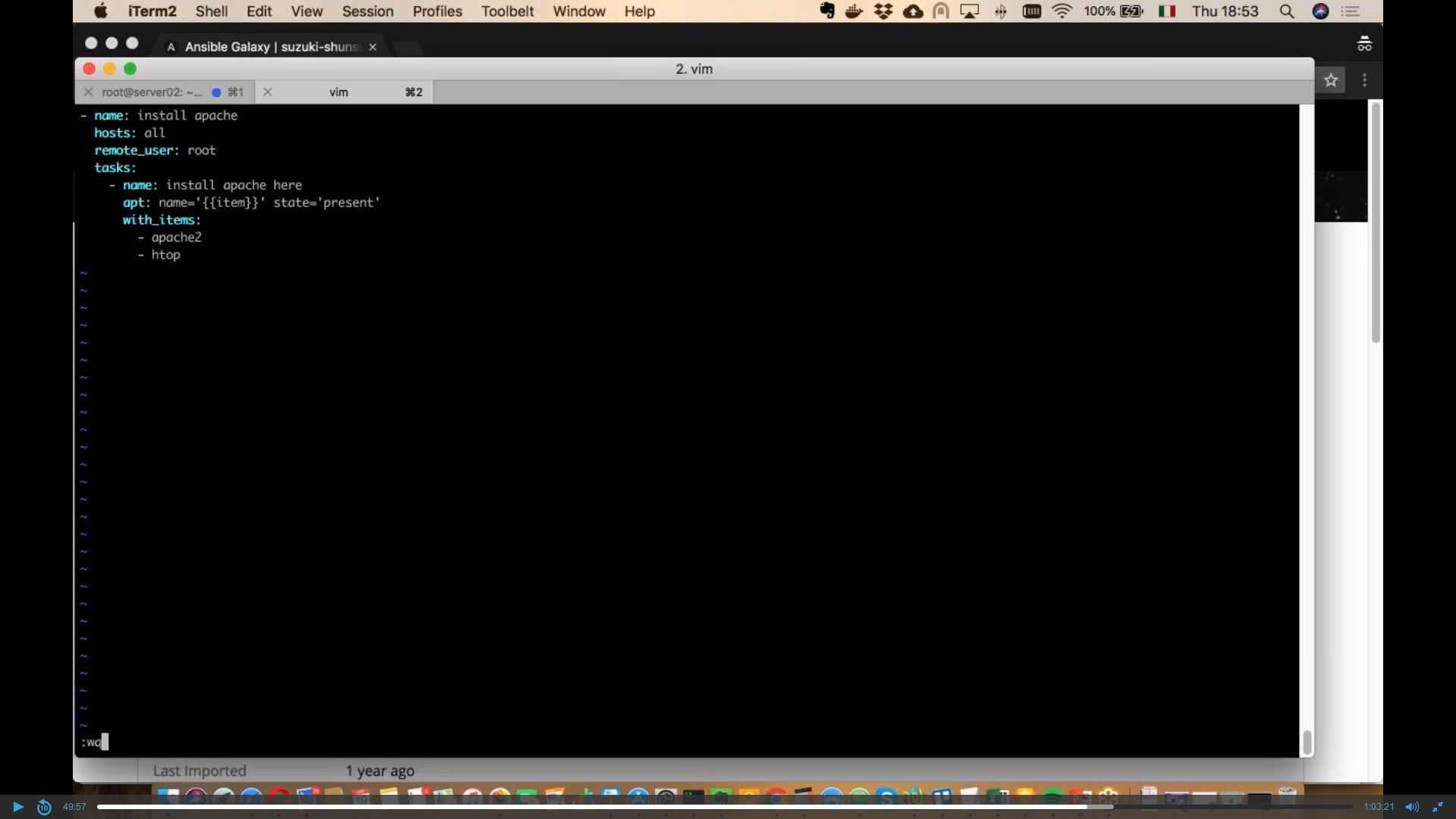

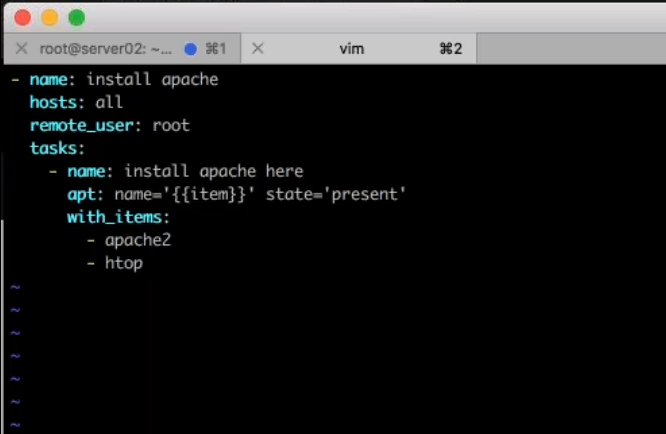

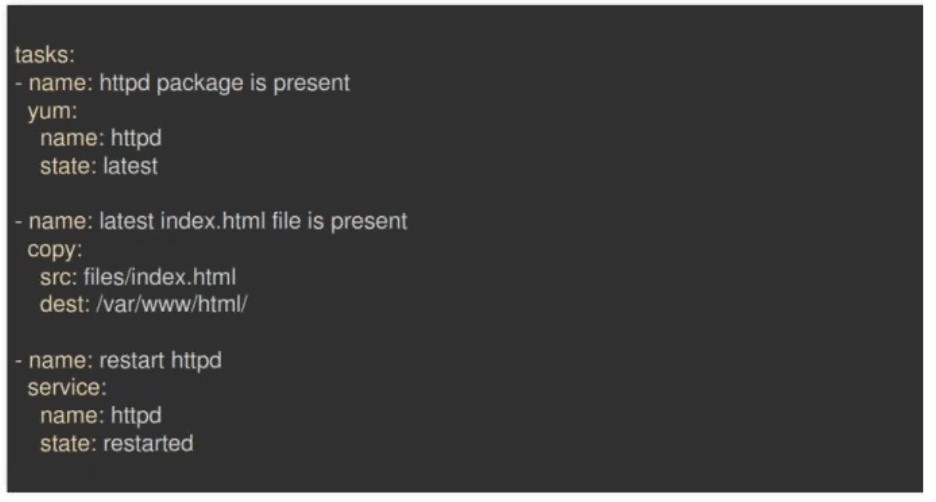

An example of playbook is portrayed in the image below, which shows the content of a YAML file which constitutes the playbook itself. This particular one actually contains a single play: this is the limit-case where play and playbook are the same thing.

The play contains two tasks with the definition of the destination hosts (host: web), the become command (with the -yes parameter stating that hosts become so after the installation) and the variables the we want to define with the -var parameter.

There are many essential features related to playbooks: Templates, Loops, Conditionals, Tags and Blocks.

Templates are files that are dynamically built according to running variables of a playbook; a typical use case is the installation of PHP: instead of creating as many playbooks as the available versions of PHP are, a Template can have a variable with the version to install. Conceptually, templates are playbook models used to dynamically set and modify variables of plays, generate files as the configuration file (with the instructions given by variables) and manage all of that with a conditional logic. Jinja2 template engine is the tool, integrated in Ansible, to build templates.

Loops can perform tasks of multiple operations, for instance to create multiple users, install software packages: bulk activities.

In the following image we’ll install a number of packages on a node using a single task instead of many; the package is httpd (latest version). The name of the task, which leverages our good old friend yum, is in quotes and in parenthesis we have the item reference to the description of the objects to install.

In other words, the command whose name is not unique but contains “{{item}} will have some parameters to be specified in the following section called with_tems. In this car you can list the name of the packages, each one preceded by a dash and on a single line as the execution is sequential.

Conditionals are the execution of tasks conditioned to state of certain conditions which are evalued at runtime like variables, facts or the result of a previous task.

For instance:

Conditionals are the execution of tasks conditioned to state of certain conditions which are evalued at runtime like variables, facts or the result of a previous task.

For instance:

- yum:

name: httpd

state: latest

when: ansible_os_family == “RedHat”

The condition dictates the task to be performed only if the remote server is a Linux RedHat distro; this allows to install a package only if the accepting OS can run it.

Tags are used to perform a subset of playbooks.

Roles in Ansible

Roles in Ansible

Roles are a set of strictly related contents that can be shared in a simpler manner than playbooks and can be used to manage and maintain complex playbooks. Roles group playbooks, files, templates with several advantages:

- Improved reliability and readibility of playbooks;

- Easier sharing, reuse and standardization of host configuration automation processes;

- Allow Ansible content to exist independently from playbooks, projects and organizations;

- Functional advantages like file path resolution and predefined values.

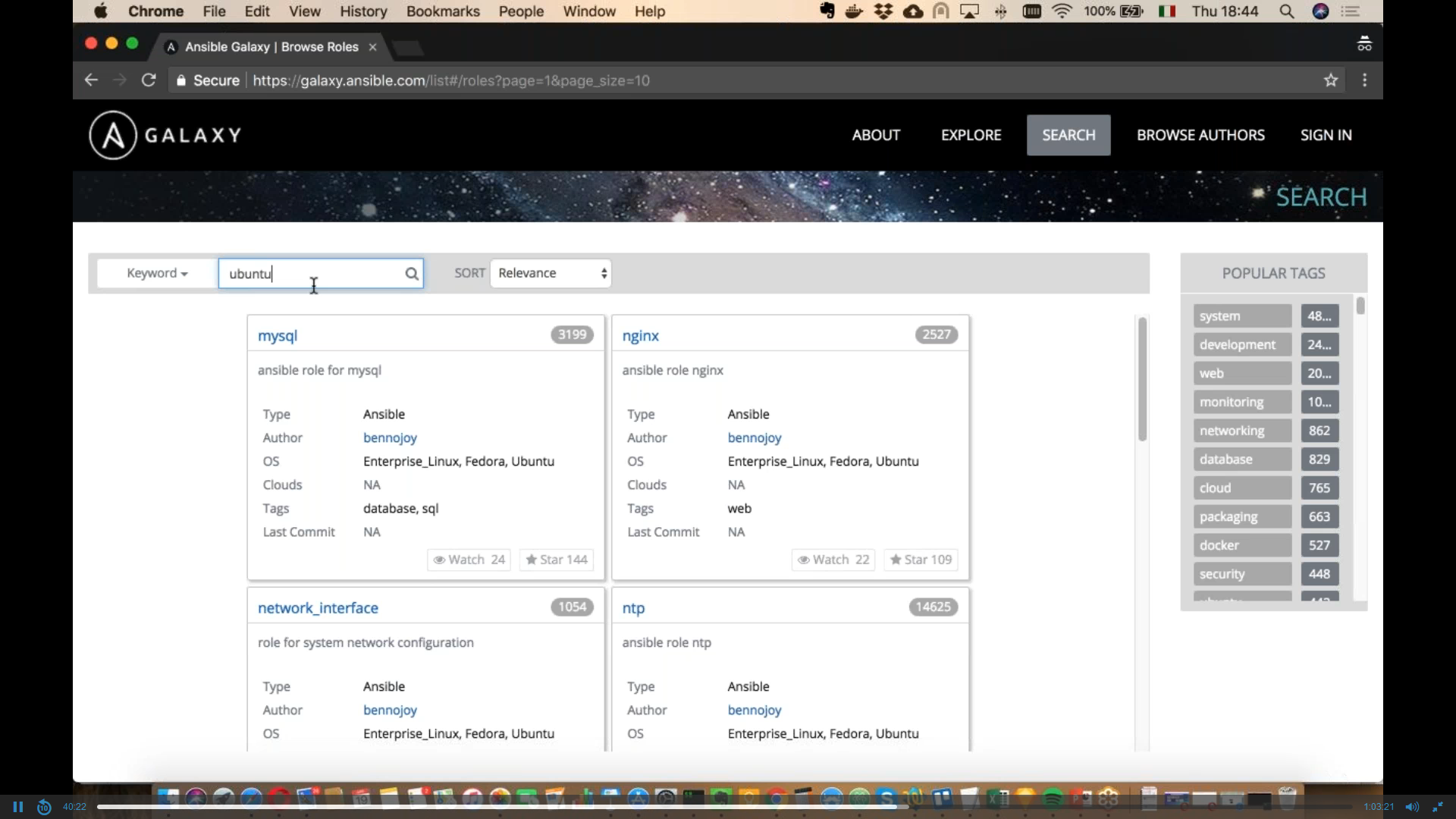

Ansible Galaxy

A very useful service is the Ansible Galaxy (https://galaxy.ansible.com) portal where you can search, reuse and share Ansible projects. This allows to realize configuration projects starting from existing modules made by members of the community, which saves time on development; it also allows developers to share their works with the community.

If you have a GitHub account you can use the same credentials on Ansible Galaxy. Before working with Ansible you’d better take a look at Galaxy as it provides many ideas and projects to get acquainted with the system.

Working with Ansible

We’ll start with Galaxy, which has examples grouped by Linux distro in the homepage.

The search function proves to be very necessary given the amount of available projects: once you find the project you like (which is on a GiHub repo), click on the name to access the repo and pull it.

Transferring and installation are done with the command ansible-galaxy install name-of-project.

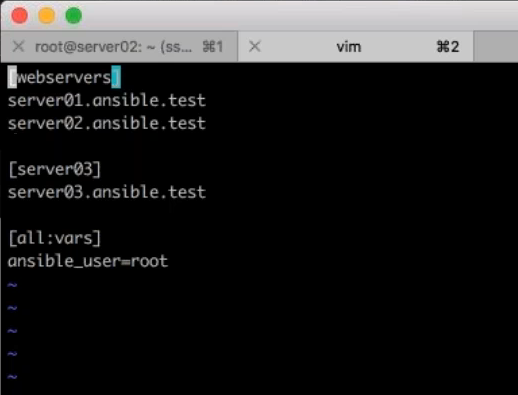

Starting from scratch, here’s a file called hosts with the following content:

The hosts file defines the network and, as the name implies, contains the names of nodes. In our example we have three nodes grouped in two groups: webservers and server03; the global variable [all:vars] defines that the user of the local computer (where Ansible runs) is authorized to operate on nodes is the root user. The variable is global as it is of the all kind.

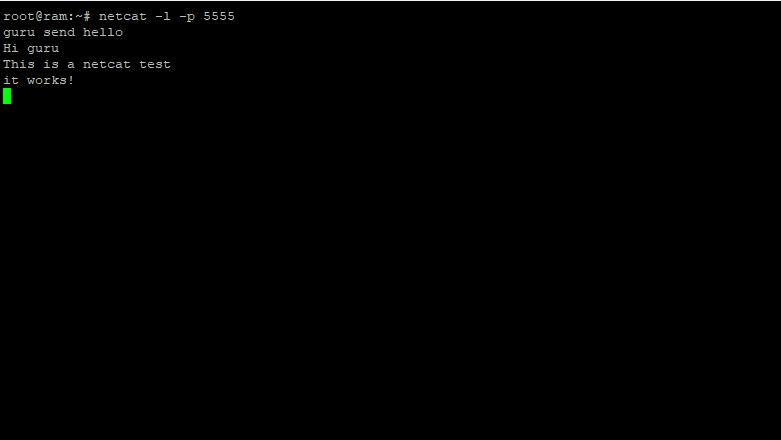

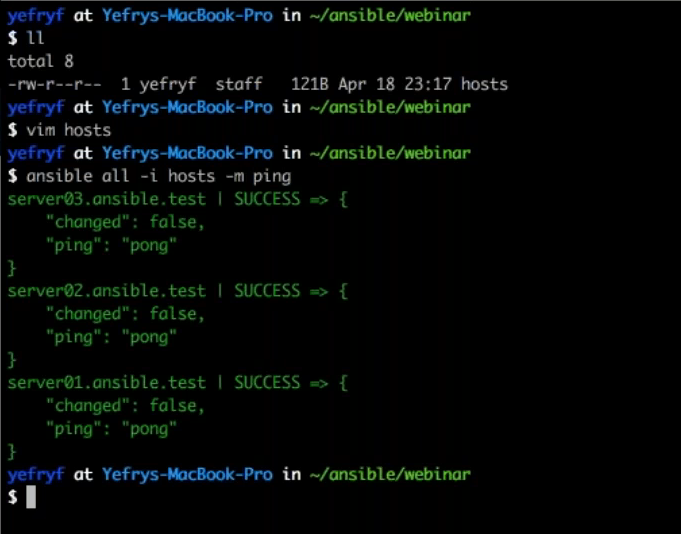

Save and close, then head back to the command line and let’s run the classic Ansible command: ansible all -i -m ping, which runs the ping module on all nodes of the Inventory. The reply should look similar as the following image.

If you want to stop the apache service on the single node of the server03 group, the command to run is:

If you want to stop the apache service on the single node of the server03 group, the command to run is:

ansible server03 -i hosts -m service -a “name=apache state=stopped2”

Where -i defined that the command is for a node of the Inventory, -m indicates the service module and -a the command of the service, which receives the “stopped” state in this case.

To restart the service on the same server, run this command:

ansible server03 -i hosts -m service -a “name=apache state=started2”

Creating an Ansible playbook

To build a playbook, start the command line and run the command, which depends on the OS, to create our file: in our case it’s apache.yml. yml is the extension of YAML files.

The installation of packages is specified with the with_items command followed by the list of packages to install. It will be performed on all nodes (hosts: all) by the remote root user. Mind the indentation!, or the Ansible will return error messages when running.

To run a playbook, use this command:

ansible-playbook -v apache.yml

Once you’ve mastered the basic mechanism you can start to build more and more complex playbooks, also thanks to the Ansible documentation and the large availability of modules. The former has detailed steps regarding the installation on any supported platform and the first use.